During our studies, we were taught the following story: “Trees in forests capture carbon. When they die and start decomposing they release all the carbon they once contained back into the atmosphere. However, by using timber in construction, we can continue to store carbon for a long time inside of our buildings.”

The story definitely sounded convincing; especially when shown pictures of thousand years old timber framed houses. But one thing bothered me. How is the forest so imperfect? Why would we need to cut trees to save the climate?

So this article was inspired by Peter Wohlleben’s book, “The power of trees,” where this narrative is dismantled and instead, a holistic and sustainable approach to forest management is explored.

- What is happening when a tree dies?

Dead trees are an essential component of a healthy forest. They are slowly broken down by fungus and host an abundance of life, including invertebrates and microbial organisms. Eventually, they are transformed into fertile humus, becoming fertilizer for future trees. The majority of the carbon contained inside the dead trees recombines inside of living organisms and the new soil. Therefore, dying trees are not CO2 emitters, but are actually helping to trap carbon inside the soil.

- What is the life expectancy of construction timber?

The picture of the 1000-year-old house is romantic, but it is far from representing the truth. On average, buildings are demolished after 70 years and all the treated timber they contain is sent to the landfill where they will release CO2.

- What is the life expectancy of a tree?

The main tree species used in the building industry is Pinus Radiata, so I will use this tree for my comparisons. However, it should be noted that this species of tree has a relatively short life span compared to other species, (especially NZ native trees). According to Farm Forestry New Zealand, Pinus radiata will commonly grow up to 150 years, 60m high with a tree trunk of 2m diameter. In comparison, a Pinus radiata grown for construction timber will be harvested after 30 years, with a height of 30 to 40m and a tree trunk of 0.6m diameter.

- How do trees capture carbon?

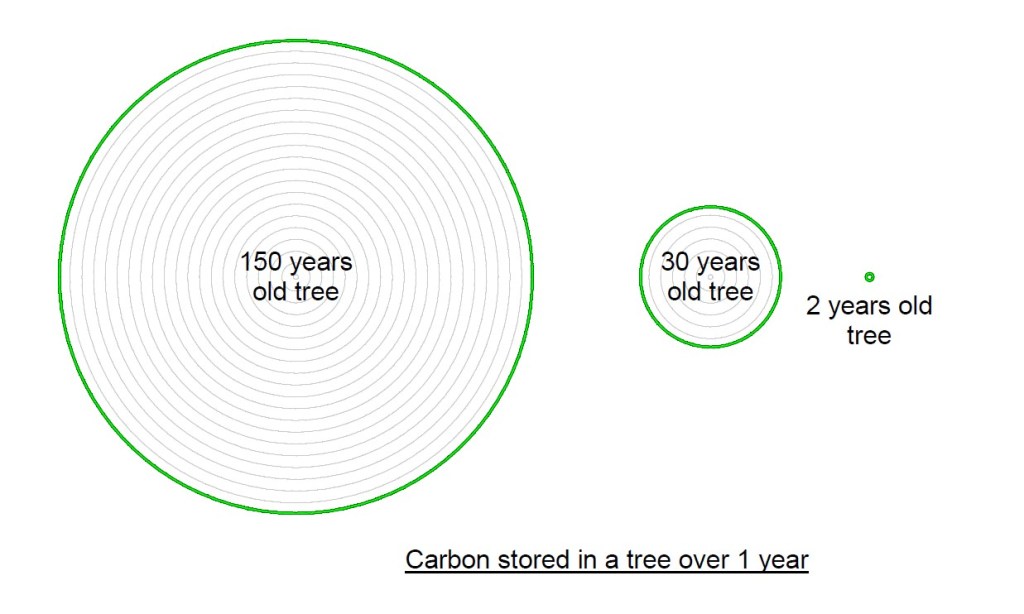

You can guess the age of a tree stump by counting the rings. Every year, a new ring is created on the outside, just under the bark. When you cut a 30-year-old tree and replace it with a new 2-year-old sapling, the amount of Carbon captured in the outer ring of the new tree will be insignificant. If instead of cutting the tree you were letting it grow, the outer ring circumference would increase every year, capturing more and more carbon.

- Is it best to store carbon in living trees or construction timber?

For a fair comparison, we should compare construction timber against the full life of a tree which has never been cut. In this case, Pinus radiata is expected to grow for 150 years. To simplify our calculations, we will only focus on the amount of Carbon stored inside the main trunk. Although, a significant amount of carbon would also be stored within the branches, roots, needles, soil, and inside living organisms hosted by this tree, (the fauna, flora, and microbial life).

Case 1: A 150 years old Pinus radiata, planted on year 0, and has been growing strong to reach 60m tall.

Case 2: Construction timber over 150 years. Planted on year 0, a Pinus radiata is harvested after 30 years and is replaced with a new sapling. This process is repeated every 30 years until year 150, resulting in 5 harvests. The first batch of construction timber was landfilled after 70 years of use on year 100, while the second batch was landfilled 30 years later, on year 130. Therefore, after 150 years, only 3 batches of construction timber are still contained within buildings.

This assumption is overly optimistic and does not account for construction waste. The additional CO2 emitted by the planting, harvesting and processing is also excluded, making the numbers for the timber construction appear much more appealing than what they really are.

Examining the section through a tree trunk alone, the area contained within a 150-year-old tree is 4.5 times larger than the area contained within 3 batches of construction timber. When you include the height of the tree, the volume increases to 6 times larger. And if you were including all the parameters ignored above, this number would be even bigger.

In conclusion, let’s be honest, using trees in construction is not a carbon pit. If the purpose was to store carbon, then we should plant trees and avoid cutting them down.

So, does this mean we should prioritize other building materials and avoid cutting trees? Well, unless you are using rammed earth or hemp, then probably not because timber is still a renewable material. However, the forestry and building industries should be more efficient in order to free up more space for wild natural forests.

Some options which could make the construction timber more sustainable:

- Trees could be harvested later. We used to harvest trees after 100 years. However, this may need to be done with local species which are able to last the distance, as introduced exotic trees in monoculture plantations can get sick easily.

- We should re-think urban planning with densification, can we renew the city every 70 years without destroying old buildings?

- Efficiency is key. We should use as little timber as possible to create the largest volume. For example: a cube is practical and efficient. Floor, wall, and roof areas should be kept to the minimum to save on resources.

- Durability and longevity should be taken more seriously; we should design low risk and low maintenance buildings that are able to be relocated.

Leave a comment